A story of survival and strength

By Emily Leighton, MA'13

Under the cover of night, the van carrying Emmanuel Ndashimye and his family approached the Rwanda-Uganda border. Alongside his mother and four siblings, he lay flat on the floor, hidden from sight and silently praying as the vehicle stopped at the checkpoint.

With no documents, they faced death if discovered. Ndashimye heard their driver speaking to border guards, but he could not understand the English words being exchanged.

Time ticked by slowly. He squeezed his eyes shut and held his breath. Suddenly, the van was moving again. The guards had waved them on without an inspection.

Immediate relief washed over the quiet, tired passengers, but hope had vanished. “There comes a point when you no longer feel life. You just accept whatever comes,” explained Ndashimye, a

Ten years old at the time, Ndashimye was escaping the terror and violence that had consumed his native country. During the course of 100 days in 1994, more than 800,000 Rwandans were killed and thousands more were displaced from their homes.

“As a child, I would be walking in the street and see people holding machetes and blunt objects, hear people screaming, see bodies being dragged and dumped,” he described. “The trucks that drove by were full of blood, it was running out of them like water. Death was everywhere.”

“It’s something you don’t want to remember, it still haunts me,” he added quietly.

As the violence escalated in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital city, Ndashimye’s family took cover in a local church each night, along with hundreds of others. Then one day as they were eating lunch at home, the sound of bullets closed in. “We knew this was it,” he said. “We left everything, even the food on the plate.”

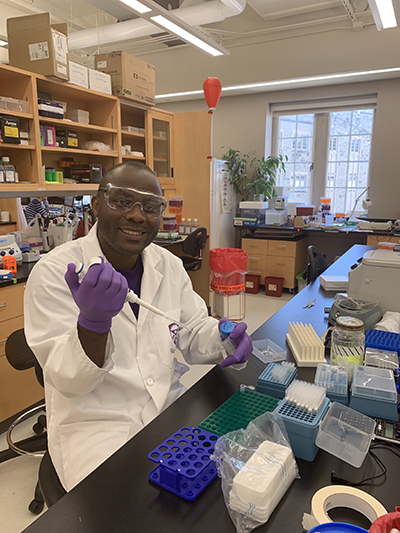

Twenty-five years after these horrific events, Ndashimye is completing his

“This is the story of who I am,” he said.

Starting over in Uganda was hard. Ndashimye’s family settled in a small remote village, focused on learning a new language, school system and rural way of life. Trained as an engineer, his father turned to

“Life was very hard, but we embraced it because we were together. We knew that to survive, we had to change,” he said.

Ndashimye and his siblings excelled in school and quickly advanced, despite being bumped back to lower grades to learn English. His parents greatly valued education and believed it was a path to a better life for their children. “Their passion became seeing us succeed in school,” he said.

As a bright and motivated student, Ndashimye moved to Mityana, a nearby town, to continue his education, renting a small room with his older brother. “We would ride the 30 kilometres back home on bicycles each weekend,” he said.

Ndashimye completed high school in Kampala and received a scholarship to study laboratory sciences at Makerere University.

During his university studies, another tragedy struck the family. Ndashimye’s father fell ill suddenly and passed away. The family buried him in the small village that had first welcomed them to Uganda.

“Without him and my mother, I wouldn’t be where I am,” he said. “They sacrificed everything.”

After graduation, Ndashimye needed to find a job to support his younger brothers, who were in primary school at the time. He found work with the Joint Clinical Research Centre (JCRC) in Kampala, providing treatment and care for HIV/AIDS patients. In his role, he coordinated research projects focused on HIV drug resistance testing.

“Seeing what HIV does to patients, it highly motivated me. Patients in Uganda are stigmatized and discriminated against," he said. "Most of them are poor, without the basic necessities of life. There is no public health insurance and antiretroviral therapy costs are high, so patients depend on foreign aid. Their stories touched me so much."

Ndashimye also had another reason to empathize so intently with patients. During a clinical placement at the end of his university degree, he had pricked his pinky finger while taking blood from an HIV-positive patient. Immediately, he started on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a medication that stops the virus from initiating infection within the body.

Side effects included abdominal pain, nausea, fever and headache. And Ndashimye got tested at the one-month, three-month and six-month marks after the incident. The experience shook the resilient, hardworking man. “I had been so strong with everything in my life, but this was going to be hard to overcome,” he said. “When the tests came back negative, it added more drive in me.”

Working in the lab at JCRC, Ndashimye met researchers from across North America, who spoke with him about the opportunities for graduate training and the promising research studies being undertaken. With this encouragement, he decided to apply for graduate school at Western.

Working in the lab at JCRC, Ndashimye met researchers from across North America, who spoke with him about the opportunities for graduate training and the promising research studies being undertaken. With this encouragement, he decided to apply for graduate school at Western.

“I wrote a statement of intent explaining who I was and what I wanted to do. I was so happy to come to Canada. My heart was telling me that I should keep doing HIV research, so this was my dream,” he said.

He received a Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Scholarship to study as a master’s student and arrived in London, Ontario

At Schulich Medicine & Dentistry, Ndashimye is focused on HIV treatment and drug resistance. “We are trying to understand why some patients fail treatment, despite having good adherence to their medication,” he explained.

There is a gap in scientists’ knowledge around why and how HIV drug resistance occurs. Ten to 15

“Finding a vaccine is challenging because we can’t reach every site that HIV has infected. The virus modifies so quickly and it establishes latent reservoirs that hide from treatment,” he said. “We know that treatment is the next best strategy, so we want to maximize the efficacy of these drugs.”

This spring, Ndashimye’s wife and young son joined him in London. “My memories can sometimes pull me down. I can wake up in the morning with a lot of emotions,” he said. “They keep me going. They put my mind at ease. My mother and siblings have also been a great influence in my life."

With such a powerful story of survival and strength, he says it’s important to focus on the things that truly matter. “Try to be happy with what you have and what you are,” he said. “We ask for much, but actually we don’t need much. To me, it’s about having what you need. If you’re with your family and friends, and you are happy, that is what life is all about.”