The Cutting Edge

Abstract

Cystic nephromas are rare benign renal neoplasms belonging to the mixed epithelial stromal tumor (MEST) family. They present diagnostic challenges due to their uncertain origin and nonspecific symptoms. Thorough sectioning, histological examination, and special staining techniques are crucial for differential diagnosis. The patient presented with a history of progressive left-sided back and flank pain, vomiting, and weight loss. Imaging revealed a large retroperitoneal mass obliterating the left renal pelvis, abutting the spleen, pancreas, and colon. The mass was removed via an en bloc resection including the left kidney, left adrenal gland, segment of colon, and distal pancreas. Gross examination revealed a fibrocystic lesion with a central cystic area and a solid peripheral

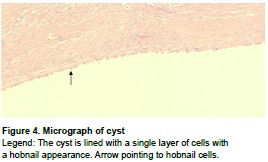

area. The en bloc nature of the specimen and uncertainty regarding malignant potential necessitated intricate sectioning. Specific staining techniques were used to aid in the diagnosis. Gross and histological examination confirmed the characteristic features of a cystic nephroma. These tumors manifest as wellcircumscribed, multicystic tumors surrounded by a thick fibrous capsule. Histologically, the cysts are lined by a single layer of epithelial cells with flat, cuboidal, hobnail, or clear-cell morphologies. Increased recognition of this benign lesion amongst the PA community is helpful for consideration of differential diagnoses and proper sampling.

Key Words: Cystic nephroma, mixed epithelial stromal tumor, renal cystic mass

Introduction

Cystic nephromas are rare benign renal neoplasms belonging to the mixed epithelial stromal tumor (MEST) family.1 They have a bimodal age distribution with the first peak occurring in males between the ages of 2-4, and the second peak more commonly in females between the fourth and sixth decades.1 Pediatric and adult-type cystic nephromas have different histopathological, immunohistochemical, morphological, and genetic hallmarks.2 Adult cystic nephromas are typically unilateral, well-circumscribed, multicystic tumors surrounded by a thick fibrous capsule.3 The cysts have thick septa which are lined by a single layer epithelium with flat, cuboidal, hobnail, or clearcell morphologies.4 The stromal cells are typically positive for estrogen/progesterone receptors (ER/

PR) and inhibin, and there is minimal cytologic atypia or mitosis.2,4 Pediatric cystic nephromas are strongly associated with DICER1 gene mutations, have thinner septa within their cysts, and are typically non-immunoreactive for inhibin.2

There is limited knowledge about the etiology, management, and progression of adult cystic nephromas. Clinical presentation can be nonspecific, with symptoms such as flank pain or hematuria, and can mimic primary renal malignancies on imaging.5 In this case report, we describe a cystic nephroma surrounded by markedly thick and extensive fibrous tissue with dense adhesions to surrounding organs. To our knowledge, this is the first report of cystic nephroma in literature necessitating a multi-organ resection.

Pertinent Patient History

A 53-year-old female patient presented to the hospital with a several-month history of severe, progressive left-sided back and flank pain. The individual experienced significant weight loss of close to 50 pounds associated with nausea and intermittent vomiting. There was no history of fever or night sweats. Computed tomography (CT) scans

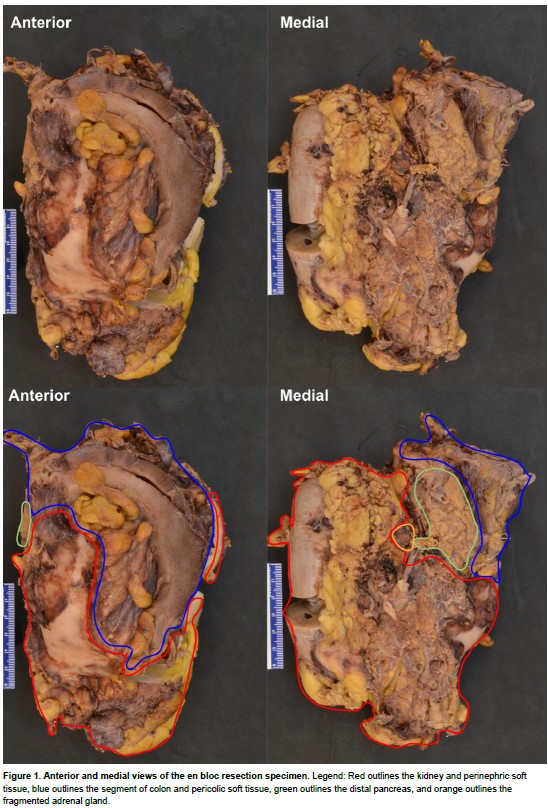

revealed a multi-septate, large retroperitoneal mass with obliteration of the left renal pelvis. The mass abutted and was adherent to the spleen, pancreas, and colon, with no radiologic evidence of direct invasion, tumor thrombus, or metastatic disease. These imaging findings were favored to represent a malignant primary renal tumor in which the best option for potential cure was excision. Given the extensive involvement of the mass, a complete resection was achieved by performing an en bloc resection including left kidney, left adrenal gland, segment of descending colon, and distal pancreas (Fig. 1). The spleen was removed and submitted as a separate specimen.

Pathological Findings

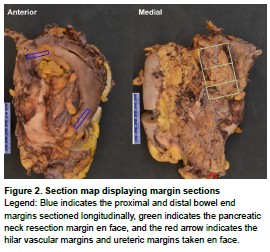

The uncertainty regarding malignant potential of the mass, along with the en bloc nature of the specimen, necessitated intricate sectioning and thorough documentation by the pathologists’ assistant (PA). The PA identified each organ and its respective margins and described main findings, including each organ’s relationship to the mass. The PA approached sectioning in an organized manner, ensuring appropriately obtained sections of each margin before cross-sectioning the remainder of the specimen (Fig. 2).

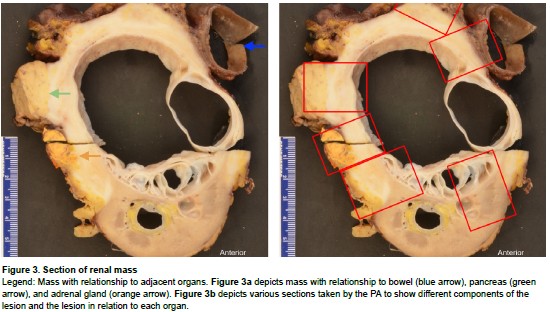

Once the margin sections were taken, the kidney was bivalved and sectioned from the superior to inferior pole. Sectioning revealed a large fibrocystic lesion (12.2 x 9.8 x 8.3 cm) that obliterated the renal sinus, pelvis, and calyces (Fig. 3a). The lesion had two distinct components: a central, multiloculated, fluid-filled cystic area (70% of lesion) and a peripheral white, solid, indurated area (30% of lesion) that replaced much of the surrounding soft tissue. The indurated areas were adherent to the colon, pancreas, ureter, and adrenal gland but did not grossly involve them. The PA meticulously cut and submitted sections of the cystic and indurated areas of the mass, mass with adjacent organs (Fig. 3b), and uninvolved sections of kidney, bowel, pancreas, and adrenal gland. A lymph node search was also conducted with all candidates submitted.

Histological examination of the indurated portion of the lesion showed extensive fibrosis with a storiform pattern in some areas and a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. There was no invasion into the adherent organs and no significant mitosis or atypia. The cysts were lined by a single layer of flat cells, cuboidal cells, and cells with a hobnail appearance (Fig. 4). The stain for PR was negative, but occasional cells did stain positive for ER.

Fibrosis with a storiform pattern and dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate are features of IgG4-related disease. IgG4 disease is a chronic fibroinflammatory disease that can manifest with tumor-like masses or enlargement of multiple

Fibrosis with a storiform pattern and dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate are features of IgG4-related disease. IgG4 disease is a chronic fibroinflammatory disease that can manifest with tumor-like masses or enlargement of multiple

organs.6 This was considered in the differential diagnosis, but when slides were stained with IgG and IgG4, the IgG4:IgG ratio was less than 40%, which did not meet the criteria for this disease. The final diagnosis was cystic nephroma, negative for malignancy.

Also considered in the differentials, besides primary renal malignancies and IgG4-related disease, were multilocular cystic renal neoplasm of low malignant potential (MCRNLMP), retroperitoneal Erdheim-Chester disease, and Castleman disease. MCRNLMPs are clinically and radiologically indistinguishable from cystic nephromas, but the specimen’s lack of clear cell morphology and presence of hobnail cells ruled out this differential. Due to the extensive fibrosis and inflammation seen histologically, the healthcare providers considered the differential

of retroperitoneal fibrosis secondary to Erdheim-Chester disease or Castleman disease.

Erdheim-Chester disease is a multi-systemic proliferation of mature histiocytes in a background of inflammatory stroma. Mature histiocytes were not appreciated in this case, nor were characteristic Erdheim-Chester bony lesions. Castleman disease is a lymphatic disorder that may result in fibrotic changes to the kidney; however, Castleman-like features such as hyaline- vascular, hypervascular, or plasma cellrich histologic patterns were not identified.

Erdheim-Chester disease is a multi-systemic proliferation of mature histiocytes in a background of inflammatory stroma. Mature histiocytes were not appreciated in this case, nor were characteristic Erdheim-Chester bony lesions. Castleman disease is a lymphatic disorder that may result in fibrotic changes to the kidney; however, Castleman-like features such as hyaline- vascular, hypervascular, or plasma cellrich histologic patterns were not identified.

Discussion

Cystic nephromas have only been described in literature around 200 times since 1892.7 The rare nature of this specimen, particularly as a multiorgan resection, led to uncertainties for the PA at the time of gross examination. On imaging, the mass appeared to be a primary renal malignancy.However, the gross appearance of the lesion did not have the typical appearance of common primary renal masses, malignant or benign. The decision was made to gross the specimen as if it were malignant, because the solid component of the lesion was abutting the surrounding organs and replacing the soft tissue.

As it was a multi-organ resection, it was important for the PA to not only describe the mass but also its relation to the segment of bowel, tail of pancreas, adrenal gland, and margins. These margins included proximal and distal bowel end margins, bowel radial margin, pancreatic tail resection margin, ureteric margin, and hilar vascular margins. Sections demonstrated the solid and cystic components of the mass, solid areas with possible extension to the bowel, pancreas, adrenal gland, and surrounding soft tissue, mass with uninvolved kidney, mass with ureter, and uninvolved sections of all organs. If this were a malignant entity such as a renal cell carcinoma variant, the extension beyond Gerota’s fascia and into surrounding organs would classify it as a stage pT4.8

With a histologic diagnosis of cystic nephroma, a benign lesion without atypia or malignancy lacking invasion into the adherent organs, one discussion point is whether the PA could have been more conservative with their sampling. Although the gross appearance was unlike common benign lesions, and there was a solid portion of the lesion abutting the colon, pancreas, and adrenal gland, the lesion looked well-demarcated from those organs; it did not appear to behave the same as other invasive, solid tumors. It could have been possible for the PA to submit fewer representative sections of the mass, but if the lesion did turn out to be malignant, it may have been more complicated to submit additional sections later. With more reports of cystic nephroma over time, its gross appearance may become more familiar to PAs, and fewer sections could be submitted more confidently. Increased awareness of this rare lesion could also lead to more research about the etiology, detection, and management of the disease, as well as the exploration of potential treatment options that could prevent the mass from becoming as extensive as the one discussed in this report.

In conclusion, cystic nephromas are rare benign lesions of the kidney with a bimodal age distribution that can mimic primary malignant kidney masses on imaging. Cystic nephromas may become enlarged and extend to adjacent organs, which necessitates thorough description and sectioning by a PA. PAs play an integral role in the preparation of tissue for histopathological diagnosis. Thus, the ability to relay all necessary information and to provide sufficient sections to the pathologist is especially crucial in multi-organ resections of unknown malignant potential. Differential diagnoses such as multilocular cystic renal neoplasms of low malignant potential or other mixed epithelial stromal tumors should be considered. It is important for PAs, pathologists, and other clinicians to learn more about this lesion to improve grossing efficiency, diagnostic confidence, and overall patient care.

References