Eyes on the Skies

The boom in Space travel poses massive challenges in keeping astronauts healthy in Space. Schulich Medicine & Dentistry researchers, faculty and alumni are already out there, carving out a leadership role for the School – a journey that has benefits for health care on planet Earth.

Welcome to the Wild West.

“It’s hard to think of another time in space exploration that was more exciting than this,” said Dr. Kris Lehnhardt, MD’03, and the top doc in the NASA Human Research Program. “The amount of investment in space ventures, the amount of interest in human spaceflight projects is unparalleled,” said Lehnhardt, Element Scientist for Exploration Medical Capability at the NASA Johnson Space Center.

A DECADE OF

INVESTMENT

US$272.2

BILLION

Total equity investment in the

Space economy over the last 10 years

1,700

COMPANIES Led by U.S., China,

Singapore, U.K. and India

CDN$2.5

BILLION

Federal funding committed in March 2023

to support Canada’s role in Space

Source: Space Capital and Health Beyond

“The number of vehicles that are designed to take people into space is more than has ever existed in our history.” The investment in space travel is astronomical: More than US$270 billion over the last decade. Space is also calling to billionaires, startups and visionaries, among them Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’ Amazon entry called Blue Origin. And just this year, Western University students created a mini satellite, slightly bigger than a Rubik’s Cube, recently launched from the International Space Station (ISS).

“It has been called the Wild West because there’s so much going on, it’s hard to keep track of everything,” said Lehnhardt, whose NASA group has partnered with dozens of companies to work on the medical side of human spaceflight at NASA. But there are dangers out there that test our ability to leave this planet. Exploring the medical solutions to these challenges is a journey Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry has been on for more than 60 years. A journey that is really just beginning.

A new dimension in space diagnosis

COVID-19 ushered in technologies like Zoom and Microsoft Teams that allowed physicians to treat patients over the phone or on two-dimensional screens.

Dr. Adam Sirek, a faculty member at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, and Western Space, and a Canadian Space Agency (CSA) astronaut candidate, added another dimension to this capability last summer. Sirek and a group of Western students, including medical student Adam Levschuk, demonstrated that holograms of a person could be virtually transmitted or holoported to another location, enabling them to interact with viewers there in 3D. Believed to be the first-of-its-kind, the technology would enable physicians to have an interpersonal conversation with a patient in another location.

Now Sirek and students are trying to take this technology to the next level.

“Our goal is to... be able to touch a hologram of a patient and literally do a physical exam remotely... This has huge implications for Space because it’s hard to fly a doctor up to Space to examine you at $80 million a rocket.”

—Dr. Adam Sirek

“Our goal is to extend it to the next phase of a clinical encounter and be able to touch a hologram of a patient and literally do a physical exam remotely,” said Sirek. “We’re working with Western Engineering Professor Ana Louisa Trejos and her amazing group of engineers to look at how to integrate actual physical feedback into a hologram.”

Here’s how their idea works: A physician on Earth could wear a virtual reality headset and a pair of gloves that can receive sensory feedback. In Space, an astronaut requiring medical care would wear a special suit or blanket that can transmit feedback to the physician’s gloves.

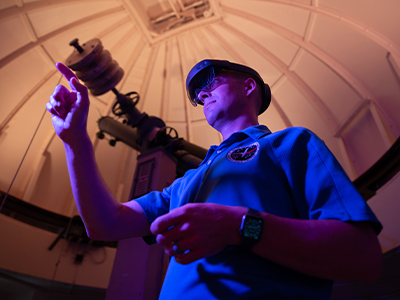

Dr. Adam Sirek demonstrates holoportation technology.

Dr. Adam Sirek demonstrates holoportation technology.

“The force I apply with my fingertips would be translated to your body virtually,” said Sirek. “I can do a physical exam remotely in order to diagnose a problem. This has huge implications for Space because it’s hard to fly a doctor up to space to examine you at $80 million a rocket.”

Holoportation has already been successfully tested on the International Space Station as part of the Ax-1 mission by Canadian Mark Pathy. But what does medical care look like beyond the space station? How do we care for patients on a journey to the Moon? Or Mars?

Solving the challenges remotely

If we could solve one key medical problem that would enable better care for astronauts going into space, what would it be?

Lehnhardt has one answer: “Help astronauts make good medical decisions, when those decisions are time-sensitive or emergent, or when they cannot talk to Earth or seek consultation from the space medicine experts on Earth.”

One solution comes in the form of a “clinical decision support system” that has the necessary capabilities – likely in an AI format that draws information from personal and ship-wide sensors – to walk astronauts through a diagnosis, determine the correct treatment and assist in that treatment. One component of this future system is called Autonomous Medical Officer Support (AMOS), which is an early module for kidney and bladder ultrasounds that was recently tested on the International Space Station (ISS).

“We asked non-ultrasound-trained astronauts to upload the software and get us medical diagnostic quality images from space. We told them, ‘Here are the tools, you figure it out.’ Then we turned off the radios.” Lehnhardt said the first few images weren’t great

But within the hour, we were getting images physicians could use to look for things like kidney stones, which is a condition that we’re worried about in spaceflight.”

Along with better resource use, like creating IV fluids onboard, NASA sees autonomy as a critical element in the transition to more Earth-independent medical operations during a deep space mission.

DANGERS OF LONG-DISTANCE SPACE TRAVEL

- Radiation exposure can increase cancer risk and damage the central nervous system

- Isolation and confinement result in sleep loss and work overload

- Distance from Earth and the length of the journey mean there’s no turning back

- Lack of gravity affects bones, muscles, and the cardiovascular system

- A closed environment can be an inhospitable home for astronauts

The future is nearly here

When Lehnhardt made his way through the medical world, armed with a passion for both space travel and medicine, he was boldly going where few Canadian medical students had gone before.

He found a home at Schulich Medicine, and advises students considering space medicine as a career direction: “If you know the area you are interested in, and it doesn’t exist, then carve your own path.”

Dr. Kris Lehnhardt stationed as NASA medical officer at McMurdo Station in Antarctica. Photo courtesy: Dr. Kris Lehnhardt.

Dr. Kris Lehnhardt stationed as NASA medical officer at McMurdo Station in Antarctica. Photo courtesy: Dr. Kris Lehnhardt.

Is there a path for medical students interested in Space?

“Yes… and no,” said Sirek, who authored a paper on the opportunities and pathways in Canada. Right now, the training path in Canada leads through the military, or overseas through the European Space Agency or in the U.S. at NASA.

“We’re going to see a huge increase in the amount of health-care research done in Space and supported by non-traditional entities, not just at NASA or the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). It’s going to be SpaceX or Axiom Space that are going to be doing this, so if you want a job at SpaceX or Axiom, you’ll have to pack up and pursue your training in the U.S.”

Meanwhile, Canada is investing heavily in our participation in Space through such initiatives as Health Beyond, leveraging our experience in providing care across long distances and our capabilities in robotics and astronaut development.

“We are thought of very well in Space circles and it’s now up to our generation and the generations following to step up and do more,” said Sirek.

WE’VE BEEN HERE BEFORE

Dr. Doug Busby, UWO MD’60, MSc’64, travelled his own path into Space medicine nearly 60 years ago. In 1964, Busby left the surgery residency program at Western to join a small group of physicians who were conducting information analyses for NASA at the Lovelace Foundation in Albuquerque, New Mexico – an institution featured in the movie: The Right Stuff.

Dr. Doug Busby, UWO MD’60, MSc’64, travelled his own path into Space medicine nearly 60 years ago. In 1964, Busby left the surgery residency program at Western to join a small group of physicians who were conducting information analyses for NASA at the Lovelace Foundation in Albuquerque, New Mexico – an institution featured in the movie: The Right Stuff.

“My first task was to identify possible medical problems from hazards of Space operations, specifically beyond Apollo and of long duration and great distance from Earth,” Busby wrote in his book, My Experiences in Medicine, Theology, and Along the Way.

During this time, Busby spent time with test pilot Chuck Yeager, consulted many scientists already working in aerospace medicine, and sat in the training capsules for Space missions from Mercury through to Apollo, and consulted on pilot safety during long-distance bomber missions. His detailed report – called Clinical Space Medicine – A Prospective Look At Medical Problems From Hazards Of Space Operations – became an important resource for the medical support of Space travel.

What was it like to work in this new environment?

“For me, my work every day was excitingly creative,” said Busby, who is optimistic that, with all of the progress made in Space medicine today, we have the ability to go on extended Space missions to places like Mars.

“I am hopeful that the velocity of future spacecraft will reduce travel times, and consequently minimize the potential for adverse effects of weightlessness and radiation on Space travellers.”