Breaking barriers: Celebrating the pioneering women who pursued their medical dreams

On International Women’s Day, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry celebrates the pioneering women – including Dr. Marie Jeanne Ferrari, one of the School’s oldest living alumni - who broke through barriers to pursue a career in the male-dominated field of medicine. And we catch up with the current generation of female medical students who are forging new paths of their own.

By Cam Buchan

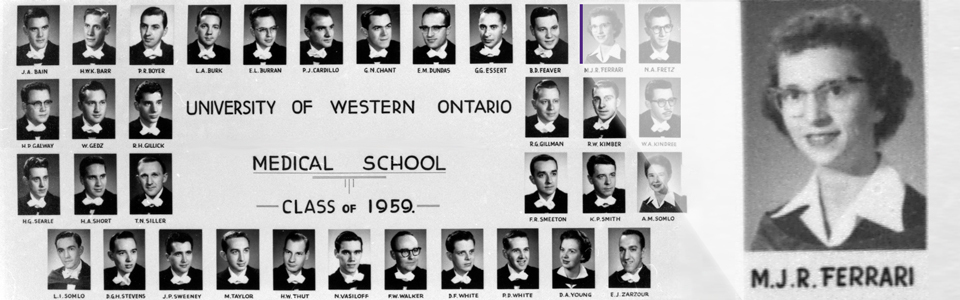

Dr. Marie Jeanne Ferrari, BA’55, MD’59

Dr. Marie Jeanne Ferrari, BA’55, MD’59

“I don’t know if I want anyone to know that. What woman tells her right age?”

With a little prodding, Dr. Marie Jeanne Ferrari, BA’55, MD’59, reluctantly admits to being 101 years old.

Among the School’s oldest living alumni, Ferrari graduated 65 years ago, one of only a handful of women in the Medicine Class of 1959.

“I applied and was accepted at the time when there was a limit on the number of women in the medical class,” said Ferrari. “They allowed 60 students in every year, and only five could be women.”

While most Canadian medical school classes have been comprised of more female students than males for several decades now – a far cry from Ferrari’s experience – Schulich Medicine & Dentistry’s medical historian points out the successes were slow in coming.

“It’s been a long road to reach these milestones and to be able to applaud the robust number of women medical students and practising physicians in Canada,” said Shelley McKellar, PhD, Hannah Chair in the History of Medicine. “International Women’s Day is the perfect occasion to recognize the achievements of women who, past and present, have contributed to increased opportunities and successes for all women.”

“International Women’s Day is the perfect occasion to recognize the achievements of women who, past and present, have contributed to increased opportunities and successes for all women.”

Gender parity has still not been reached among the number of physicians working in Canada, McKellar said, but adds it’s “only a matter of time” until that happens.

THE PRIVILEGE OF MEDICAL SCHOOL

Ferrari’s journey began in Tecumseh, Ontario, where she was born in September 1922. “A little town near Windsor, you may or may not have heard of it.”

It wasn’t long before the desire to become a doctor took hold of the Tecumseh native. Inspired by the biography of brothers Charles and William Mayo, who were part of the group that founded the world-famous Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, Ferrari applied to faculty of medicine.

“They were brave and they were daring and they overcame many obstacles,” Ferrari said of the Mayo brothers.

Unsuccessful in her first application to Western, she turned to pharmacy, at the advice of her father, who said being a pharmacist was the next best thing to being a doctor.

“I completed my training in pharmacy, and then worked for a couple of years. But, the desire to be a doctor still nagged me. So, I reapplied,” she said. “At that point, I had two degrees, a BA in Arts and my pharmacy degree. I think maybe that’s how I got in, because I was older than the other students by that point.”

It was an era of exciting discoveries at the School when Ferrari came to the Ottaway Ave. (South Street) location. A graduate of Western's medical program in 1947, Carol Whitlow Buck had recently received her PhD in the Department of Clinical Preventative Medicine, and – most importantly for women – earned the position of Head of the Department of Community Medicine in 1967. The world’s first delivery of cancer radiation therapy to patients using a “cobalt bomb” was done in 1951. And Dr. Charles Drake pioneered a surgical procedure to correct cerebral aneurysms in 1958.

Shelley McKellar, PhD

Shelley McKellar, PhD

Ferrari became a doctor in the face of certain restrictions and hurdles, said McKellar, who leads the History of Medicine program at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry and is also professor in the Department of History.

“How daunting it must have been for women to pursue a career in medicine if they numbered only a few, surrounded by male classmates, and taught by male instructors,” she said.

But despite these limitations, Ferrari thoroughly enjoyed her time at medical school.

“It's difficult to put my finger on exactly what was so great about it,” she said. “First of all, I enjoy learning and I really wanted to be a doctor. I liked my classmates, they were great. Our male counterparts treated us with great respect. I don’t think anybody had any complaints about anybody else. We were there to learn to become good doctors and that was it.”

After graduation, Ferrari did a five-year residency in Internal Medicine.

I SAW THE WORLD

But for all her training, she only spent a short time practicing. She worked for two years at Memorial Hospital for Cancer and Allied Diseases, New York, and two years at Tulane University in New Orleans, before going to the University of Ottawa as an epidemiologist in the Department of Public Health.

“I mean, I saw the world!”

She certainly did. During her residency at Memorial, Ferrari served at a hospital on Turtle Island, off the north shore of Haiti, while the regular physician was on medical leave. On arrival at Port de Paix, Ferrari crossed over to the island, “in a sailboat manned by what looked like pirates.” She recalled the straw mats on the floor of the hospital, lack of modern medicines, and poor conditions.

“I remember setting a compound fracture of the tibia, using only morphine as an anaesthetic. The poor man!”

After working for the federal government in immigration medicine, Ferrari retired at age 70. But her desire to learn continued to motivate her. She entered the field of Canon Law – the laws governing the Catholic Church – and earned her degree, an aspect of her faith she still enjoys. Ever up for a challenge, Ferrari also adopted three children and fostered four others, all as a single mom.

“It was a great privilege to be in medical school.”

Three of her children still live in the Ottawa area, and she sees them every Sunday for dinner.

“You have to realize, I never got married. I feel it was the grace of God that I was able to adopt those children,” she said.

Yet for all of her adventures, Ferrari is reluctant to see herself as a pioneer.

“I don’t really feel like one. Maybe this surprises you, but it was a great privilege to be in medical school,” she said. “I haven’t had a boring life. It's been fun. Oh, and I thank God for that. I thank God for that. Yes, indeed.”

REPRESENTION

Despite Ferrari’s reluctance to view herself as a trailblazer, women in the School’s current medical class were quick to point out that early female representation, like Ferrari’s, laid the groundwork for them to pursue medicine as a career.

Umaima Abbas

Umaima Abbas

“I am inspired by women like Dr. Marie Ferrari who helped to break new ground for the next generation of women like myself,” said Umaima Abbas, a second-year student at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry’s Windsor Campus and vice-president, Windsor, of the Hippocratic Council.

“Despite being in a class with only five women in the program, Dr. Ferrari's courage and resilience paved the way for women in medicine by reminding us that our identity should never limit our career aspirations,” said Abbas, the first woman in her family to pursue post-secondary and professional education.

Christina Lim

Christina Lim

Christina Lim, who came from the world of Engineering, is also part of a new generation of women who are seeing changes in the medical world. Yet they acknowledge the contributions that women of the past have made to their successes.

“Representation is such an important part of empowering youth to pursue careers or academic opportunities, like medicine,” said Lim, a second-year medical student and vice-president, Communications, of the Hippocratic Council. “It’s hard to be what you can’t see. Now as a Southeast Asian woman, when I see staff physicians who look like me or come from backgrounds like mine, I can envision myself in their shoes and feel as though I belong.”

Lim is using the problem-solving skills learned in Engineering and applying them to solutions that are closer to her heart. As well, she hopes to become a mentor to future students.

“I think mentorship is one of the ways I feel most empowered as a female student, and I would like to pay that forward to future students interested in pursuing medicine.”

“It’s hard to be what you can’t see. Now as a Southeast Asian woman, when I see staff physicians who look like me or come from backgrounds like mine, I can envision myself in their shoes and feel as though I belong.”

Abbas is grateful to see how far women have come in the field. But there’s more work to be done.

“I couldn't be more grateful to have fellow women colleagues by my side. Continuing to advocate for women's voices, both in medical education and in our patient population, will be one of my top priorities as a future physician.”

A look back at the early pioneers from Schulich Medicine & Dentistry’s past

Dr. Dorothy Kathleen Braithwaite (Sanborn)

Western University's First Female Medical Student

Dorothy Kathleen Braithwaite was born in llderton in 1900. Graduating from London Collegiate Institute with a Senior Matriculation Certificate in 1917, Dr. Braithwaite went on to receive a Bachelor of Arts degree from Western University. In March of 1918 the Executive Committee at Western passed a resolution to admit women into the Faculty of Medicine using the same regulations and requirements for men. Braithwaite entered the program and in 1924 she received her Medical Doctor certification. After a two-year internship at City Hospital in Buffalo and Victoria Hospital, Braithwaite opened a practice in Windsor with her husband Clare S. Sanborn, also a graduate of Western's medical program.

Carol Whitlow Buck

First Woman to Attain Full Professorship and Department Head

A graduate of Western's medical program in 1947, Carol Whitlow Buck received her PhD in the Department of Clinical Preventative Medicine for her work done under the guidance of Dr. G. E. Hobbs. Upon her graduation, Whitlow received an appointment at Western as an assistant professor. Further training at the University of London allowed Whitlow the opportunity to attain full professorship in 1962. Whitlow held many titles during her career at Western; however, the most ground breaking for women was the position she received in 1967 as Head of the Department of Community Medicine. In 1972, after the division of the Department of Community Medicine, Whitlow became Chair of the Department of Epidemiology and Preventative Medicine.