Adventurers retrace trek of gold-seeking trio featuring Western medicine school co-founder

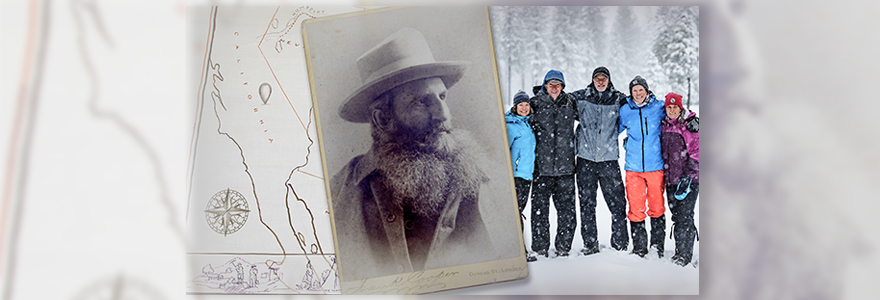

A team of endurance athletes with a passion for history (right background) are retracing the harrowing gold-seeking expedition of Western medical school co-founder Dr. Richard Maurice Bucke (foreground) and Allen Grosh across the Sierra Nevada mountains, starting Monday, Feb. 27, 2023. (Map, Archives and Special Collections/Western Libraries; photo by Frank Cooper/Western Archives and Special Collections; design by Andrew Campbell/Western Communications)

By Keri Ferguson, Western News

Long before becoming a prominent Canadian psychiatrist, author and co-founder of Western’s medical school, Dr. Richard Maurice Bucke achieved another feat – as sole survivor of a harrowing gold-seeking expedition through the Sierra Nevada mountains in 1857.

Bucke set out on the trek with Hosea and Allen Grosh, who believed they had found the Comstock Lode. However, both brothers died before they could claim it at the assayer’s office in San Francisco. Hosea, the youngest, struck his foot with a pickaxe early on and died of blood poisoning. Allen, distraught with grief, vowed to continue, with Bucke by his side – and many of his papers and maps left behind in his cabin, entrusted to the care of Henry Comstock.

Now, more than 150 years later, a team of five endurance athletes are retracing Bucke and Allen Grosh’s 100-mile route across the Sierras. Driven by an appreciation of the character and motivation of these hopeful pioneers, they also wish to share important new historical information and maps, gleaned with help from Western’s Archives and Special Collections (ASC) team.

The Grosh Brothers Expedition team. From left, Elke Reimer, Hal Hall, Tim Twietmeyer, Bob Crowley, and Jennifer Hemmen. (History Expeditions)

The Grosh Brothers Expedition team. From left, Elke Reimer, Hal Hall, Tim Twietmeyer, Bob Crowley, and Jennifer Hemmen. (History Expeditions)

The athletes departed from Gold Canyon, Nevada on Monday, Feb. 27, and a GPS tracking system will trace their five-day trek to Last Chance, California.

Western’s health, medicine and science archivist Anne Quirk will be watching their journey with interest, having worked with Crowley’s teammate Hal Hall since last August, providing prudent information accessed through the Dr. Richard Maurice Bucke and Family fonds and those of Bucke’s son-in-law, Dr. Edwin Seaborn. With the help of archives assistant Theresa Regnier, Quirk saw more than 600 documents scanned and sent to the expedition team within a fairly tight timeline.

“Requests for scans of archival records are not uncommon, but this request was unusual, because of the intended use of the information,” Quirk said. “Most people who contact us are conducting academic research or writing a book. In this case, the team from California were using the information to recreate this expedition as closely as possible to the original one from 1857, and they came to us because Bucke was the only survivor.”

‘Bucke’ing the trend

Bucke stood out throughout his life, largely known for his contributions at Western and to his field, and for his magnum opus, Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind.

As medical superintendent at what was then known as the London Asylum for the Insane from 1877 to 1902, Bucke was a pioneer of mental health care, favouring physical and social therapies over restraints and heavy medication. He initiated an open-door policy, allowing patients the freedom to walk the institute’s well-kept grounds.

Bucke was also a devoted fan of Walt Whitman, adopting the American poet’s style of dress. He even reached out and befriended Whitman, and later hosted him at his London, Ont. home for a three-month stay in 1880.

It was with similar gumption and optimism that Bucke set out to see the world at 16 years of age. He took many odd jobs across the United States before landing in California, washing gold from the sands of Gold Canyon. That is likely where he first met the Grosh brothers. Like Bucke, they were sons of clergyman. They were also well educated, with considerable knowledge of chemistry and metallurgy.

“I think, intellectually, they would have appealed to Bucke,” Quirk said, making them a match for the journey ahead.

Loss of lives and limbs

The group’s original plan was to make their way across the Sierra Nevada mountains from south of Virginia City, Nevada to Last Chance. From there, they aimed to carry on to Sacramento, then San Francisco.

Anne Quirk, archivist, Western Archives and Special Collections (Chris Kindratsky/Western Communications)

Anne Quirk, archivist, Western Archives and Special Collections (Chris Kindratsky/Western Communications)

But Hosea’s death marked what became an ill-fated and unfinished journey right from the start. Allen and Bucke encountered rain and then a series of early winter storms, becoming trapped in Squaw Valley for days.

Bucke writes of a “fine, bright day,” that followed, allowing them to finally reach the summit of present-day Watson Monument. Exhausted and starving, they made their way to an empty cabin in Little America Valley, known as the Greek Hotel. Bucke, who had been in the cabin before, hoped they’d find rations there, but the cupboards were bare. With yet another storm upon them, they stayed in the cabin for two days.

Venturing on, they became weaker as they travelled in circles, losing their way. They threw away items weighing them down, including a gun too wet to fire and a packet of Allen’s ore samples and papers. Allen also stuffed his maps and assay records in a hollow of a large tree, with both men memorizing its location before staggering on.

“What strikes me is how Bucke knew how close he was to death,” Quirk said, pointing to a journal passage where he wrote, “Let us make up our bed for the last time, for we shall never leave this place. I am done for, so let me die.”

After four days without food, and with legs frozen from above the kneecap down, the pair crawled toward a mining ditch, where, upon seeing cabins up ahead, Bucke uttered, “Our troubles are over,” before collapsing in the snow.

He and Grosh were discovered near death by two miners, who carried them on sleds to Last Chance. At last, they were warm and dry, yet severely frostbitten and suffering from starvation. With gangrene setting in, and without antiseptic, a miner used his hunting knife to amputate Bucke’s left foot, and part of his right. Both of Allen’s legs were amputated before he fell into a coma and died.

Once nursed back to health, and through funds raised by the miners, Bucke was sent back to Canada. He went on to study medicine at McGill University and pursue post-graduate studies in Europe before settling in London with his wife, Jessie Gurd.

What he didn’t forget was his near-death journey, or his fellow prospectors. Years later, he had a headstone shipped and carried by mule train to Last Chance, to mark the grave of his friend. The marker remains there today, where the 2023 expedition crew will conduct a quiet ceremony on their last day.

Crowley credits Quirk and the archives team “for assisting us in providing convincing evidence that we used in writing an article that changes the historical narrative 175 years later,” he said.

On supporting the team’s mission, Quirk says, “We’re very happy to be involved and to help them as much as we could,” noting Bucke’s key role in this important piece of history. “He was the only survivor, a fighter, and he lived to tell the tale.”

For more about Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry’s history, visit our archives.