Western researchers make breakthrough in arthritis research

Monday, December 3, 2012

Researchers at Western University have made a breakthrough that could lead to a better understanding of a common form of arthritis that, until now, has eluded scientists.

According to The Arthritis Society, the second most common form of arthritis after osteoarthritis is "diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis" or DISH. It affects between six and 12 percent of North Americans, usually people older than 50. DISH is classified as a form of degenerative arthritis and is characterized by the formation of excessive mineral deposits along the sides of the vertebrae in the neck and back. Symptoms of DISH include spine pain and stiffness and in advanced cases, difficulty swallowing and damage to spinal nerves. The cause of DISH is unknown and there are no specific treatments.

Now researchers at Western University's Bone and Joint Initiative, with collaborator Doo-Sup Choi at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota have discovered the first-ever mouse model of this disease. The research is published online in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

"This model will allow us for the first time to uncover the mechanisms underlying DISH and related disorders. Knowledge of these mechanisms will ultimately allow us to test novel pharmacological treatments to reverse or slow the development of DISH in humans," says corresponding author Cheryle Séguin of the Skeletal Biology Laboratories and the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at Western's Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry.

Graduate student Derek Bone, working under the supervision of pharmacologist James Hammond, was studying mice that had been genetically modified to lack a specific membrane protein that transports adenosine when he noticed that these mice developed abnormal calcification (mineralization) of spinal structures.

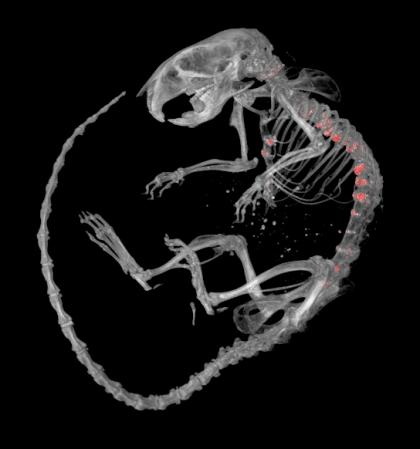

Changes in the backbone of these mice were characterized by an interdisciplinary team, which included graduate student, Sumeeta Warraich, technician, Diana Quinonez, postdoctoral fellow, Hisataka Ii, imaging scientists Maria Drangova and David Holdsworth, and skeletal biologist, Jeff Dixon. Their findings established that spinal mineralization in these mice resembles DISH in humans and point to a role for adenosine in causing abnormal mineralization in DISH.

These studies were funded by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Canadian Arthritis Network (CAN). Séguin is supported by a Network Scholar Award from The Arthritis Society and CAN.

Micro-CT image of mouse skeleton, showing excessively mineralized lesions (in red) along the spinal column and sternum (breastbone).