From acute to chronic, David Seminowicz is researching the problem of pain

By Cam Buchan

Cuts and bruises. Stomach aches and migraines. Like the rest of us, David Seminowicz, PhD, has experienced the aches and pains of living, including catching the tip of his finger in a car door.

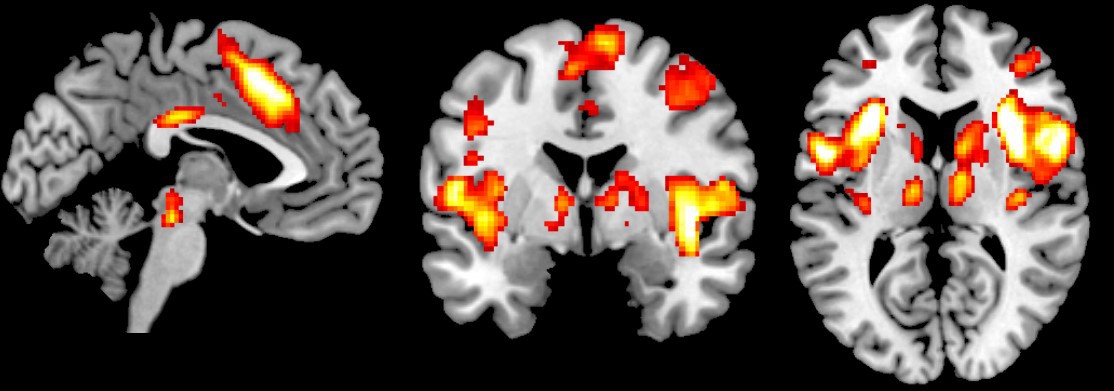

Studies of the brain using MRI scans have given us a good deal of information about acute pain – the day-to-day type that comes and goes – and the areas of the brain that are involved in it, such as the somatosensory cortex, insula, anterior cingulate cortex, some brain stem areas and the thalamus, he said.

“Using a scanner and evoking pain, we can get a reliable set of activations in the brain across a large number of individuals,” said Seminowicz, a researcher at Robarts Research Institute and The Brain and Mind Institute. “Then through various therapeutic manipulations or distractions, we can see how the brain reacts.”

Now his research is also leading him into the realm of chronic pain, those conditions such as back pain, migraine, rheumatoid arthritis or temporomandibular disorder (TMD) that can last for months, years, or even a lifetime.

MRI scan showing the areas of the brain involved in sensing intense pain. Average of 42 subjects experiencing intense (~7-10) pain. (Image provided)

MRI scan showing the areas of the brain involved in sensing intense pain. Average of 42 subjects experiencing intense (~7-10) pain. (Image provided)

A global journey

Seminowicz has essentially crossed the globe before coming to Robarts and Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry.

As a doctoral student at the University of Toronto, Seminowicz studied mood and affective disorders through the use of imaging. But a talk by Karen Davis, PhD, at the University of Toronto made him realize there was considerable shared circuitry in the imaging of the brain done by pain and depression researchers, and his career took a turn in a new direction.

Beginning at the University of Maryland, he researched a mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program for migraines, which uses such elements as yoga and meditation. In this work, imaging was done on patients prior to and after they had undergone a 16-week mindfulness program adopted from a treatment for depression and anxiety. The results showed that mindfulness appears to be an effective treatment for those suffering from migraines. Seminowicz is still following up with further studies to better understand what makes this treatment work.

From there, he went to Neuroscience Research Australia at the University of New South Wales, where Seminowicz and his colleagues looked at temporomandibular disorder, a condition that causes pain in the jaw joint and in the muscles that control jaw movement and affects millions worldwide. Seminowicz looked to assess the brain biomarkers of TMD to identify people who were susceptible to developing this type of chronic facial pain. Seminowicz hopes the study will lead to the development of a predictive tool that can be used to identify patients who are at risk for developing chronic TMD and who may benefit from early intervention and treatment.

The problem of chronic pain

“Pain is essentially the number-one reason people seek primary care. It’s what brings people to the doctor. Unresolved pain is very burdensome to the person and often means they’re laid up with a disability and can’t continue to work.”

The complete pain experience has sensory, cognitive and emotional components, said Seminowicz. Pinch your finger, and sensory fibers are activated that travel through the spinal cord and into the brain telling you it hurts. But it doesn’t stop there: the cognitive component draws your attention to the pain, while the emotional element tells you this experience is unpleasant.

Chronic pain is a multi-faceted problem, because people suffering ongoing pain also tend to disengage from society, which brings with it emotional and mental challenges.

There are still many questions to answer, and the work begun in Australia continues. Seminowicz is hoping to develop baseline measurements to predict who is most likely to be highly sensitive to pain.

“Currently, the best predictor we have of who is going to develop persistent pain following surgery is how much pain someone has immediately following surgery. At that point, it’s a little too late because they are already in severe pain. But if we could predict who is likely to develop more pain, we could take more aggressive pain management strategies at the pre-operative stage to better manage the pain post-op.”

Seminowicz is also looking at pain management outside of the traditional pharmaceutical solutions, which links back to his work with mindfulness techniques.

“There's lots of evidence linking high stress, anxiety, and depression levels with increased pain. We can reduce all those things with MBSR. Mindfulness can also help manage ongoing pain, too, so it's a multi-pronged therapeutic.”

But still, the problem of pain persists, and it’s one that keeps his attention, even in the daily aspects of life.

“I caught the tip of my finger in the car door, and it was amazing how such a tiny little injury could be so painful and fully consume my attention.”