Oral health research goes modern

By Emily Leighton, MA’13

Would you let a barber pull your teeth?

In the Middle Ages, lay barbers practised tooth extraction in addition to the conventional shaves and haircuts. This approach was phased out by the 18th century, and the world’s first dental college, the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery, was founded in 1840. Today, the modern dental office is an ode to technological innovation with high-tech digital tools such as laser probes and 3D x-rays.

Despite this professional transformation, Dr. Walter Siqueira, professor in Dentistry and Biochemistry, believes there is a lasting perception of dentists as “tooth technicians” rather than specialized oral health care providers and biomedical scientists.

In Canada, dentistry also remains separate from other areas of health care and isn’t included in the Canada Health Act. This, despite compelling evidence of the link between oral health and systemic health. In a landmark report published in 2000, then-U.S. Surgeon General David Snatcher called the problems of oral health around the world “a silent epidemic promoting the onset of life-threatening diseases.”

The country also lacks a government-funded institute dedicated to oral health research, such as the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research in the U.S, one of the 27 institutes and centres under the National Institutes of Health. This creates unique challenges for research funding and representation.

“There’s a pervasive attitude that no one dies because of their teeth,” explained Douglas Hamilton,

“We spend $14 billion on cavities and tooth decay each year in this country, which comes from the pockets of Canadians, not the government,” added Dr. Siqueira.

As president-elect of the Canadian Association of Dental Research, an organization that represents the oral health research community across the country, Dr. Siqueira believes dental research is an essential investment, one that will help the profession overcome some of these larger challenges.

Although there are challenges, Drs. Siqueira and Hamilton represent a strong oral health research culture at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry. Both were awarded Project Grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) in 2018, receiving two of only four oral health research projects that were funded across the country in the Spring 2018 competition.

With his own research program, Dr. Siqueira is creating a novel drug delivery systems to prevent and treat tooth decay. It is work that may eventually change the composition of our everyday use products, from toothpaste to soft drinks.

During previous research projects funded by NSERC and CIHR, the researcher discovered that salivary proteins bond together to form a protective shield against bacteria in the mouth. Using bioinformatics, he was also able to predict the evolution of the salivary proteins throughout millions of years, observing that they grow stronger in the fight against bacteria.

Dr. Siqueira and his team took this information and created salivary proteins that resembled these older, evolved versions. “The proteins we’ve created have far more power than the proteins that we currently observe in saliva now,” he explained.

With the results of these two previous projects and knowledge about the physiology of the mouth, Dr. Siqueira, working with Elizabeth Gillies,

The constructed nanoparticle reacts to the lower pH levels, opening and releasing the specialized protein that kills bacteria and protects the tooth. When the pH is restored to normal levels, the nanoparticle closes. One nanoparticle can remain in the mouth and cycle through the process for up to six hours.

Dr. Siqueira and WORLDiscoveries reached an agreement to license and patent the technology. He envisions it being delivered not only through typical dental hygiene products like toothpaste, but also soft drinks and even candy.

“We need to work in different ways to protect people’s teeth, and this type of delivery system is very personalized to the individual,” explained Dr. Siqueira. “Why not work with products that people enjoy to better protect their teeth?”

This type of innovation is just one of the many that

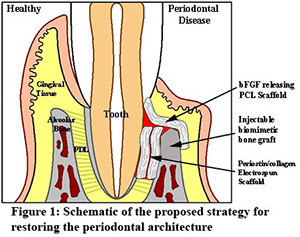

As a researcher, Hamilton likes to think outside the box. With his Project Grant, he is focusing on developing novel membranes to be used in guided tissue regeneration, a technique used in the treatment of periodontal disease. Collaborating with Drs. Amin Rizkalla, Les Kalman, DDS’99, and Mark Darling, he is developing biomaterials that will shift the balance toward regeneration rather than repair of the alveolar bone, gingiva and periodontal ligament.

As a researcher, Hamilton likes to think outside the box. With his Project Grant, he is focusing on developing novel membranes to be used in guided tissue regeneration, a technique used in the treatment of periodontal disease. Collaborating with Drs. Amin Rizkalla, Les Kalman, DDS’99, and Mark Darling, he is developing biomaterials that will shift the balance toward regeneration rather than repair of the alveolar bone, gingiva and periodontal ligament.

"Current membranes used in guided tissue regeneration often give unpredictable results, and significant advances can be made in the bioactivity of the membranes, which is our focus," Hamilton explained. "By using molecules important in the normal periodontium that cells recognize, we think tissues can be regenerated."

Periodontal disease begins as a bacterial infection in the gums, known as gingivitis. If untreated, the infection can spread and destroy structures that support the teeth and jawbone. It is linked to a number of health issues, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes and respiratory illnesses.

“Periodontal disease gives you a window into a person’s overall health, and can sometimes point to undiagnosed systemic health issues,” explained Hamilton.

“Periodontal disease gives you a window into a person’s overall health, and can sometimes point to undiagnosed systemic health issues,” explained Hamilton.

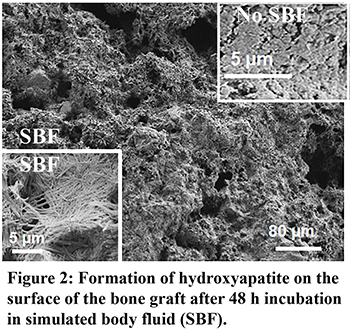

The research team is designing new membranes to restore bone height in cases of periodontal disease. They have also developed a novel bone graft material that is injected into the defect as a liquid but sets quickly to form a bone substitute that bonds to

The approach is cost-effective, safe and shows potential for quick translation to the clinical setting. And the ease of the procedure means periodontists won’t have to be retrained.

Clinical collaboration is a must in today’s research climate says