In an age when AI can draft medical reports, detect cancer on scans and accelerate drug discovery, it’s no surprise the scalpel is getting smarter, too. Across research labs and operating rooms, a wave of surgical innovation is transforming how – and when – surgeons operate.

But innovation isn’t always robotic arms and machine learning. Sometimes, it’s a bold decision made in the operating room. A new way of seeing anatomy. Or a moment where instinct and experience guide the hand.

At the front lines of this evolution are surgeon-scientists at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry. Their work offers a window into the future of surgery – one that blends technology with judgment, data with experience and precision with a profoundly human touch.

The Future Has Your Back

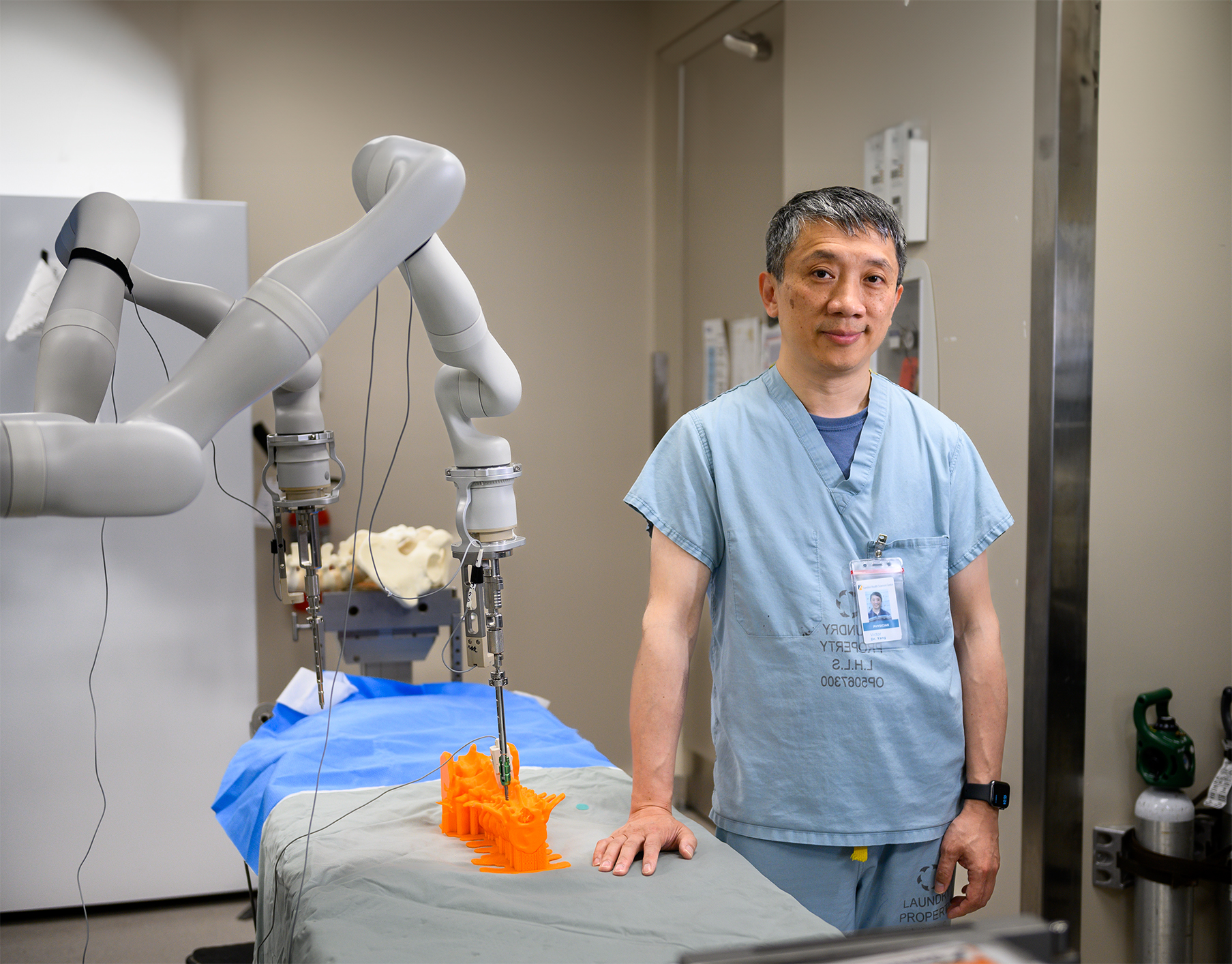

“The best outcomes happen when surgeons do what we do best – plan and lead the surgery – while robots handle the repetitive tasks.” — Dr. Victor Yang

The surgeon’s assistant moves with calm precision – never hesitating, never trembling. Every motion is deliberate, every incision exact.

Peering down at the operating table, one arm leans in with a high-precision screwdriver, placing a screw into the spine to stabilize the vertebrae.

But this isn’t a surgical resident. It’s a cutting-edge robot that’s set to make back surgery safer and more efficient.

“Robots are so much better than humans at repetitive, sequential tasks, like drilling holes and placing screws,” says Dr. Victor Yang, a neurosurgery professor, surgeon and prolific inventor, who has spent the last decade perfecting the ideal robotic spinal surgery assistant in his lab.

What sets his robot apart from others, Yang says, are its humanoid eyes to see and two hands to work with pinpoint accuracy – crucial in procedures where millimetres matter.

"Spinal surgery is a very delicate procedure, designed to help people regain mobility and decrease pain,” says Yang. “Accurately providing surgical care is paramount to giving our patients the best possible chance at a successful outcome.”

As both a surgeon and scientist, Yang sees himself as a bridge between the lab and the operating room – something evidenced by the dozens of patents he holds for medical devices. His goal is to continue the research in first-in-human clinical trials.

Still, the London Health Sciences Centre surgeon – who also boasts a degree in engineering – doesn’t believe robots will ever replace surgeons.

“The best outcomes happen when surgeons do what we do best – plan and lead the surgery – while robots handle the repetitive tasks,” Yang says.

Setting a New Beat

“I don’t just want to do what’s worked in the past, I want to innovate for the future to advance care for our patients.”

— Dr. Michael Chu

As a child, Dr. Michael Chu lived with an irregular heartbeat. The palpitations were frequent and unexplained – so familiar, he didn’t realize how sick he was.

Everything shifted when a team of specialists in London, Ont. diagnosed the issue and treated it with a then-experimental catheter-based ablation technique.

“It was transformative,” he says. “I didn’t know what normal felt like until I got better.”

The minimally invasive procedure not only restored his health, it sparked a lifelong drive to push the boundaries of surgery.

Now chair and division head of cardiac surgery and the Ray and Margaret Elliott Chair in Surgical Innovation at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry and London Health Sciences Centre, Chu is focused on making heart surgery safer and more effective for patients.

His research spans innovative valve repair, hybrid aortic reconstruction and transcatheter techniques that replace open-heart procedures with endoscopes, wires and catheters, small incisions and faster recoveries.

During the pandemic, Chu’s team also redesigned the delivery of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) procedures – cutting hospital stays from four days to same-day discharge and tripling the number of patients treated daily. “Sometimes innovation isn’t a new device – it’s rethinking what you already have,” he says.

Chu, who completed his cardiac surgery residency at the School, leads the Canadian Thoracic Aortic Collaborative and holds cross-appointments in anatomy and cell biology, and biomedical engineering. But it’s the patient in front of him, and the one he used to be, that keep him motivated.

“I don’t just want to do what’s worked in the past,” he says. “I want to innovate for the future to advance care for our patients.”

Precision in the Veins

“Sometimes the most important innovations are basic, The point isn’t to do something new, it’s to do something better. If it means the patient has a safer, shorter recovery, that’s the goal.” — Dr. Audra Duncan

For decades, repairing the aorta meant opening the chest and racing the clock – a high-risk procedure that often hinged on speed and luck. That’s now changing, thanks to a technique with a name as strange as it is life-saving: frozen elephant trunk.

Part open surgery, part catheter-based repair, this hybrid technique allows surgeons to reconstruct the aorta in a single, carefully staged operation.

Leading this change is Dr. Audra Duncan, chair and division head of vascular surgery, who has helped make the procedure safer and more widely used in Canada.

For Duncan, surgical innovations like this are rooted in outcomes, not optics.

“Sometimes the most important innovations are basic,” she says. “The point isn’t to do something new, it’s to do something better. If it means the patient has a safer, shorter recovery, that’s the goal.”

The same principle guides her approach to treating rare conditions like Nutcracker syndrome, a painful disorder in which the left renal vein is compressed between two major arteries. While robotic and laparoscopic repairs are gaining traction, Duncan still prefers open surgery. It offers greater flexibility and allows her to tailor the procedure in real time – something that machines can’t yet replicate.

“You don’t really know what you’re working with until you get in there,” she explains. “If there’s too much tension on the vein or unexpected anatomy, robotic tools just won’t cut it. I need to see it and feel it in order to fix it.”

With each case, Duncan weighs more than just technical criteria, she considers recovery, frailty and future quality of life.

“There’s an art to this work,” she says.

The London Health Sciences Centre surgeon is also leading efforts to gather gender-specific data in vascular surgery – particularly in aortic dissection, where outcomes for women remain under-researched and poorly understood.

“There’s no single right answer in surgery,” she says. “You have to know the tools, know the science, and then know your patient.”