Mind the gap

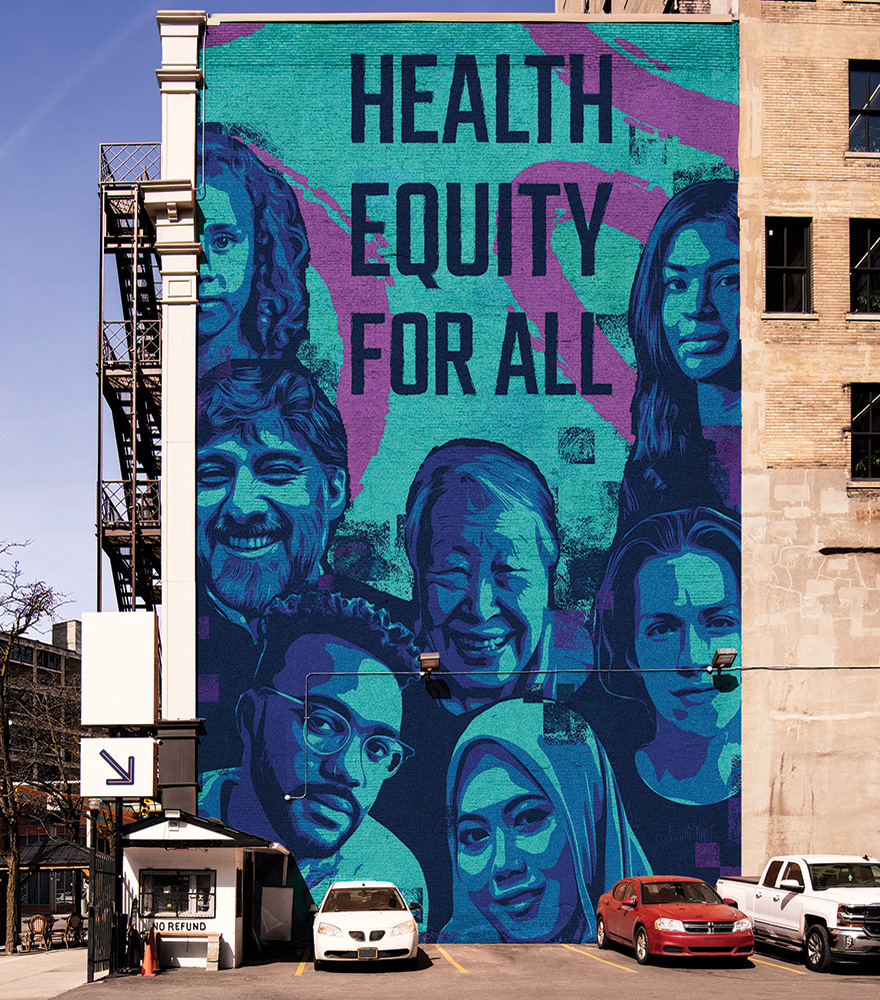

Despite our national system of health insurance, not every Canadian has equal access to high-quality care – a concern that many faculty and alumni are working to address

By Crystal Mackay, MA’05

When Dr. Samir Sinha, MD’02, Director of Geriatrics at Sinai Health System and the University Health Network, was a medical student, he spent summers conducting research in a remote Indigenous community in northern Manitoba.

“Prior to that time, I had been doing work to raise awareness of poverty and health issues in developing countries, not fully appreciating that we have significant health equity issues within our own borders.”

It was a realization that stayed with him and continues to shape his career today. And he’s not the only one: many Schulich Medicine & Dentistry alumni, faculty and learners focus their work on how to ensure equitable access to health care for all Canadians. The challenges are deep and seemingly intractable, but research is helping to point the way forward.

“We have a universal health care system that isn’t really universal. It doesn’t meet the needs of older Canadians who are responsible for more than half our health care spending. Older people are physiologically different. They need their care to be approached through a different lens.”

— Dr. Samir Sinha

Sinha points out that the much-vaunted Canadian Medicare system was created in the 1960s to serve a young and relatively healthy population. While physician and hospital care were covered, many other services were not. “We have a universal health care system that isn’t really universal,” he said. “It doesn’t adequately meet the needs of older Canadians who are responsible for more than half our health care spending.”

Of 92,000 physicians in Canada today, fewer than 400 are geriatricians, yet one in five Can-adians is now an older person. Complicating this challenge is the fact that aging Canadians are a diverse group, including LGBTQ+ people, newcomers, and racialized and Indigenous populations. The lack of high-quality long-term and home care means that as many as 15 per cent of hospital beds are currently occupied by older people who don’t need acute care but can’t return home or get into a long-term care home.

“Care required to relieve pain and infection is essential to one’s quality of life and productivity. But research suggests that the impacts go further. Poor oral health impacts the type of jobs you can get, and the amount you earn.”

— Dr. Carlos Quiñonez

In addition to increased investment in the services that older people need, Sinha wants to ensure that all medical students have basic training in geriatrics. “Older people are physio- logically different,” he says. “They need their care to be approached through a different lens.”

Maria Mathews, PhD, Professor, Family Medicine, has focused much of her research on access to care for people living in rural and remote communities.

During her time at Memorial University, Mathews studied the issue of recruiting and retaining physicians in rural communities. She found that only one-third of graduates of Memorial University’s medical school practise in the province. Instead, many communities depend on international medical graduates, who are able to practise in rural settings while completing licensing requirements. But research suggests that once fully licensed, many move to other locations in Canada.

Mathews has also explored the impact of financial incentives to encourage graduates to practise in smaller communities. Again, the effect is modest.

In one study, Mathews and her team looked at the impact of high physician turnover on residents’ health. They compared rural communities with high retention rates to those with high turnover rates. They also included so-called ‘no-doc’ communities where a nurse or nurse practitioner provides care, with a doctor visiting regularly. Interestingly, the study showed comparable results in high retention and no-doc communities. “This is an exciting result,” Mathews said. “It suggests that there may be a different approach for rural communities; one that provides health care that is just as good as having a resident doctor.”

“In fact, we have evidence that they are unique survivors – people who are courageous, entrepreneurial, and committed to building a better life for their families.” — Dr. Kevin Pottie

In a soon-to-launch study, Mathews is looking at the outcomes of a unique interdisciplinary clinic in London that helps family physicians manage diabetes patients, especially when equity issues, such as insecure housing, mobility challenges or low income, are involved. “We want to evaluate whether this kind of care model is cost effective and could be considered for other chronic diseases.”

Dr. Carlos Quiñonez, Vice Dean and Director of Dentistry, focuses his leadership and research around inequities in access to oral health care. While most Canadians have access to dental care through employer-sponsored insurance, 20 to 30 per cent of Canadians say they can’t afford dental care.

Care required to relieve pain and infection is essential to one’s quality of life and productivity, Quiñonez says, but research suggests that the impacts go further. “Poor oral health impacts the type of jobs you can get, and the amount you earn,” he said.

People who can’t access dental care because of cost often end up in hospital emergency departments and doctors’ offices; what he calls “an inefficient and ineffective use of health resources.” While some political parties are calling for dental care to be added to Canada’s publicly funded health care system, Quiñonez says the problem is complex, with many stakeholders and high political and economic costs. “There is no single solution.”

“Health is not just an end goal. It is a resource that enables people to be educated, get good jobs, and have a decent quality of life.” — Maria Mathews, PhD

Among current research, his team is evaluating a project providing dental care at no cost to working poor families at a Toronto clinic funded by Green Shield Canada. Another study looks at defining what medically necessary or essential dental care actually means. A third study will develop a rigorous economic model for government-provided dental care.

Dr. Kevin Pottie, MCISc’01, Professor, Family Medicine and Ian McWhinney Chair of Family Medicine Studies, is one of the early members of Médecins Sans Frontières Canada and has taken part in several international humanitarian missions. His experiences have led to a special interest in health equity for immigrants, refugees and people experiencing homelessness.

He notes that some physicians are reluctant to accept these patients into their practices. “Canadian doctors are not immune to feeling uncomfortable when dealing with different peoples,” he said. “They may also be concerned about medical and legal risk, and worried about challenges of working through interpreters and across cultures. But there are also many physicians who enjoy the human richness that comes from working with diverse populations.”

Recognizing that new Canadians have unique care needs, Pottie has led a network of Canadian researchers in developing evidence- based clinical guidelines for treating immigrants and refugees. In 2020, his team also produced guidelines for the care of the homeless and vulnerably-housed.

He points out that providers often see refugees as helpless and dependent, bringing developing world problems with them. “In fact, we have evidence that they are unique survivors – people who are courageous, entrepreneurial and committed to building a better life for their families.”

During the European migrant crisis, Pottie worked with the World Health Organization and led the development of the European Migrant Health Guidelines. His experience is especially valuable now, as Canada prepares to accept large numbers of refugees from Afghanistan, Iraq and Myanmar. Most recently, he and his colleagues have produced provider guidance for Ukrainians seeking shelter in Canada.

As Mathews points out, health equity is about more than physical and mental wellness. An immigrant herself, she looks to the experience of her grandmothers, who left school to provide care for family members. “Health is not just an end goal,” she said. “It is a resource that enables people to be educated, get good jobs, and have a decent quality of life.”