A new breed of clinician-researcher

Double the roles. Double the responsibility. Double the passion.

Clinician-researchers have been a part of Schulich Medicine & Dentistry’s core for decades. With a recent push to focus on translational research, and to take part in more collaborative projects, a new breed has emerged—they are vibrant, open-minded, and full of exciting new ideas that will, undoubtedly, change the course of medicine.

Dr. Bill Clark, professor in the Department of Medicine, and clinician-scientist in the Program of Experimental Medicine, believes that by nature of having the dual roles, clinician-researchers are in the perfect position to develop and discover innovations that will improve the quality of life for patients.

He’s also a strong supporter of the increased focus on research during undergraduate and postgraduate medical training. “I think by training clinician-researchers at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry, we’re developing a vanguard of individuals who will not only be able to practise clinical medicine, but will also be able to develop discoveries and innovations that will improve the whole aspect of health care,” he said.

By Jesica Hurst, BA’14

Dr. Samuel Asfaha

“When you go from working on basic research to the clinic where a patient has run out of treatment options, it’s hard not to be inspired and go back to the lab with more motivation.”

Dr. Samuel Asfaha grew up wanting to do basic research, but he also always wanted to be a clinician. He didn’t know how to choose between his two passions.

During the first year of his undergraduate education, he found out he could make a career out of doing both. He has never looked back.

After spending the past few years working at Columbia University in New York, Dr. Asfaha and his family decided to move back to Canada in October 2014 so he could continue his research at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry. He now serves as a gastroenterologist, clinician-scientist and assistant professor in the Department of Medicine and Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. His main research focus is on inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) and colon cancer.

“I am trying to identify stem cells in the colon with the goal of trying to find the cellular origin of cancer,” Dr. Asfaha said. “Once I can identify that cell, I can better appreciate what regulates it and understand how inflammation affects the cell to lead to cancer.”

IBD patients are predisposed to increased risks of cancer. However, researchers do not currently understand why some patients with IBD develop cancer while others do not. Because of this, all IBD patients are recommended to undergo colon cancer surveillance on an annual basis.

“If we can identify and differentiate patients based on this stem cell, this would be important clinically because we could have a more effective way of screening patients and predicting outcomes,” he said.

Dr. Asfaha explained it is easy to stay passionate and committed to his work when it has a translational application. While he does simply love trying to address challenging questions, his goal has always been to better understand problems that have a clinical impact.

“For someone who likes to address challenging questions and also provide good care to patients, it’s an unbelievably unique and rewarding job,” he said.

Dr. Arlene MacDougall

“We are using the interventions I’m developing and studying in the clinic with real patients—it doesn’t get more translational than that.”

Dr. Arlene MacDougall has the best of both worlds.

Working as a clinician-researcher with the Department of Psychiatry and as a psychiatrist with the Prevention and Early Intervention Program for Psychoses she has been able to follow her dream of helping people, promoting health, and looking into system-level questions about how to improve the field of medicine.

“What I see on a day-today basis clinically helps guide me in my research, as it’s easier to identify how we could possibly improve treatment and develop new programs to better serve patients,” she explained. “Likewise, I’m interested in translational research, so I can see the potential application in a clinical environment.”

While she didn’t necessarily set out to become a clinician-researcher, she has always had an inquisitive mind and wanted to involve herself in a multi-faceted career. It’s the ability to have these different facets that keeps her passionate and stimulated in her career.

Dr. MacDougall’s main research focus is a project entitled Community REcovery Achieved Through Entrepreneurism (CREATE). Based in Kenya, CREATE will develop a business designed to employ people with mental illness and will provide an accompanying toolkit of psychological and social support that promotes recovery and successful reintegration into society.

She is also leading two other highly translational research projects. One is looking at youth-focused mindfulness group intervention for people with early psychosis, while the other is using participatory video as a way of engaging people with early psychosis to help them develop a narrative about their experience with illness.

“I feel like being a clinician-researcher is the way I can have the most impact in my career. That is what I’m focused on— making an impact and creating real-world change,” she said.

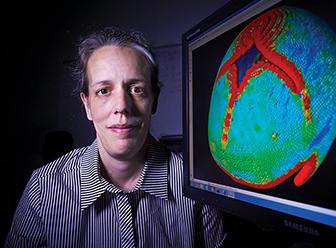

Dr. Sandrine deRibaupierre

“If you’re passionate about helping patients, and you’re always questioning things and trying to find answers, becoming a clinicianresearcher is a good path to follow.”

“Being a clinician alone is pretty boring for me,” Dr. Sandrine deRibaupierre said with a laugh. “When you’re training, it’s great because you’re learning something new every day. But after that, most cases you see are similar and the growth you experience is restricted.”

That’s why the paediatric neurosurgeon loves research. She can return to the fundamental questions of “why does this happen” and “how can we do this better”—the creative, innovative part of her job.

Growing up and completing her training in several countries throughout Europe, Dr. deRibaupierre never expected to settle down in London, Ontario. It was the flexibility and collaborative environment at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry that brought her on board in 2008. In addition to her clinical practice, she is now an associate professor in the Division of Neurosurgery at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry.

“In general, people here want to collaborate more than they want to compete, which is not the case in other places,” she explained. “As a clinician, I don’t have as much time to dedicate to my research so I rely on collaboration to make things more efficient.”

When she’s not on call, in the clinic or in the operating room, Dr. deRibaupierre focuses on two main areas of research.

The first involves designing new surgical simulators, as well as evaluating commercial simulators used to help train residents. If she can discover how to teach residents better using simulation, it would have a significant impact on resident competence and patient safety.

Her second research focus involves observing normal brain behaviour and the variability of different brains using functional magnetic resonance imaging.

“Working on research that is translational and related to the clinical work you’re doing really feeds your questions,” she said. “I think I’m a better clinician because of my research.”

Dr. Christopher McIntyre

“Myself and other new clinician-researchers have deliberately avoided going in the direction of prestige and expertise. We’re going in a direction outside of our comfort zone—the collaborative area between specialties.”

When Dr. Christopher McIntyre took a position in Derby, England, he was given what can only be described as a dingy office. No windows, no lights, and only one door that opened up to a main waiting room for a dialysis unit, Dr. McIntyre naturally spent a fair bit of his time watching patients as they would come and go for their treatment.

“They arrived pink, talking and happy, and would leave pale, grey and silent,” Dr. McIntyre said. “It was that empirical observation that something was happening to them during treatment, which has led me to my current research endeavours.”

Dr. McIntyre recently joined Schulich Medicine & Dentistry’s team as a clinician-scientist and professor in two departments: Medicine and Medical Biophysics. His work, simply put, is focused on two goals—helping dialysis patients have fewer symptoms, and die less. He hopes that his research can be a driving force in achieving these goals.

Dialysis patients have approximately the same risk of dying as most cancer patients, and for those who live, there is a tremendous burden of symptoms on the quality of life. Most of these issues come from the dialysis treatment itself. Dr. McIntyre has found that by reducing the temperature of the dialyzate—the part of a mixture that passes through the membrane in dialysis—they can prevent drops in blood pressure, and protect the heart and brain.

Next year, he will launch the largest study ever completed with dialysis patients worldwide to test this discovery. It will involve approximately 7,500 patients.

Even though his contract officially splits up the time he spends on research and the time he spends as a clinician, Dr. McIntyre explained projects like these prove his work is more blended than compartmentalized.

“If you do research like I do, it’s hard to see where one role ends and the other role begins,” he said. “In that way, the scheduling seems artificial because when I’m working on my research, I’m helping my patients, and vice versa.”