“The goal of my work is to design new ways to prevent HIV transmission, which could have a significant impact on the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa.”

- Jessica Prodger, PhD

By Max Martin, MMJC’19

Since the 1980s, HIV has remained one of the world’s most widespread epidemics. More than 70 million people have been infected with the virus, and more than 32 million have died.

Today, 37.9 million people are living with HIV.

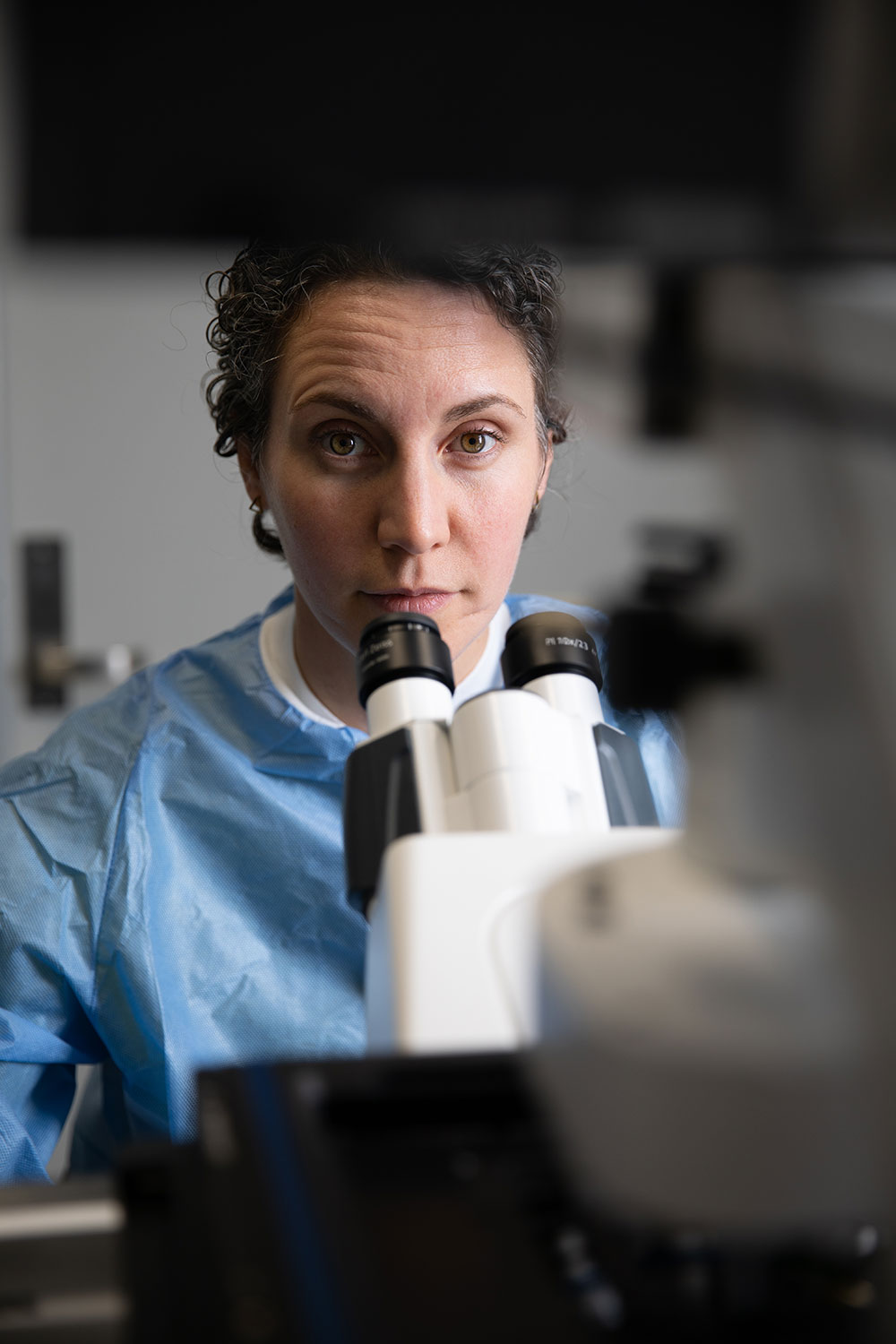

Inside the containment labs of Western University’s Imaging Pathogens for Knowledge Translation (ImPaKT) Facility at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry, Jessica Prodger, PhD, is undertaking a novel approach to preventing HIV transmission.

“The goal of my work is to design new ways to prevent HIV transmission, which could have a significant impact on the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa,” said Prodger, Assistant Professor, Department of Microbiology & Immunology.

Her team is investigating why certain individuals are more or less susceptible to HIV. She’s exploring how the penile microbiome, or the polymicrobial community that lives on the surface of the penis, may contribute to HIV transmission in heterosexual men.

“Certain bacterial communities on the penis make it easier, or harder, for HIV to established infection,” Prodger explained. “My research is focused on understanding the interplay and communication between the penile microbiome and the human tissues, and how the relationship between bacteria and human cells can influence a virus.”

“The goal of my work is to design new ways to prevent HIV transmission, which could have a significant impact on the HIV epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa.”

- Jessica Prodger, PhD

The research is building off the observation that circumcision reduces a heterosexual man’s chances of contracting HIV by about 60 per cent. But the question of why this intervention is effective remains unanswered.

A high abundance of anaerobic bacteria – microbes that thrive in oxygen-deprived areas – are usually present under the foreskin of an uncircumcised man. These anaerobes are often associated with subtle, asymptomatic inflammation. As a part of this inflammation, the body recruits immune cells, like CD4 T-cells, which are susceptible to HIV infection. This means anaerobes could be triggering a series of events that increase the likelihood of HIV transmission.

Prodger hypothesizes that circumcision is increasing oxygen on the surface of the penis, which decreases the anaerobes and shifts the polymicrobial community, reducing HIV susceptibility.

Now, she’s working to demonstrate causality and discover which microbes are causing the inflammation to develop transmission prevention tools.

“We want to tease out exactly which anaerobes are causing problems so we can selectively remove just those and leave the rest of the penile microbiome intact,” Prodger explained.

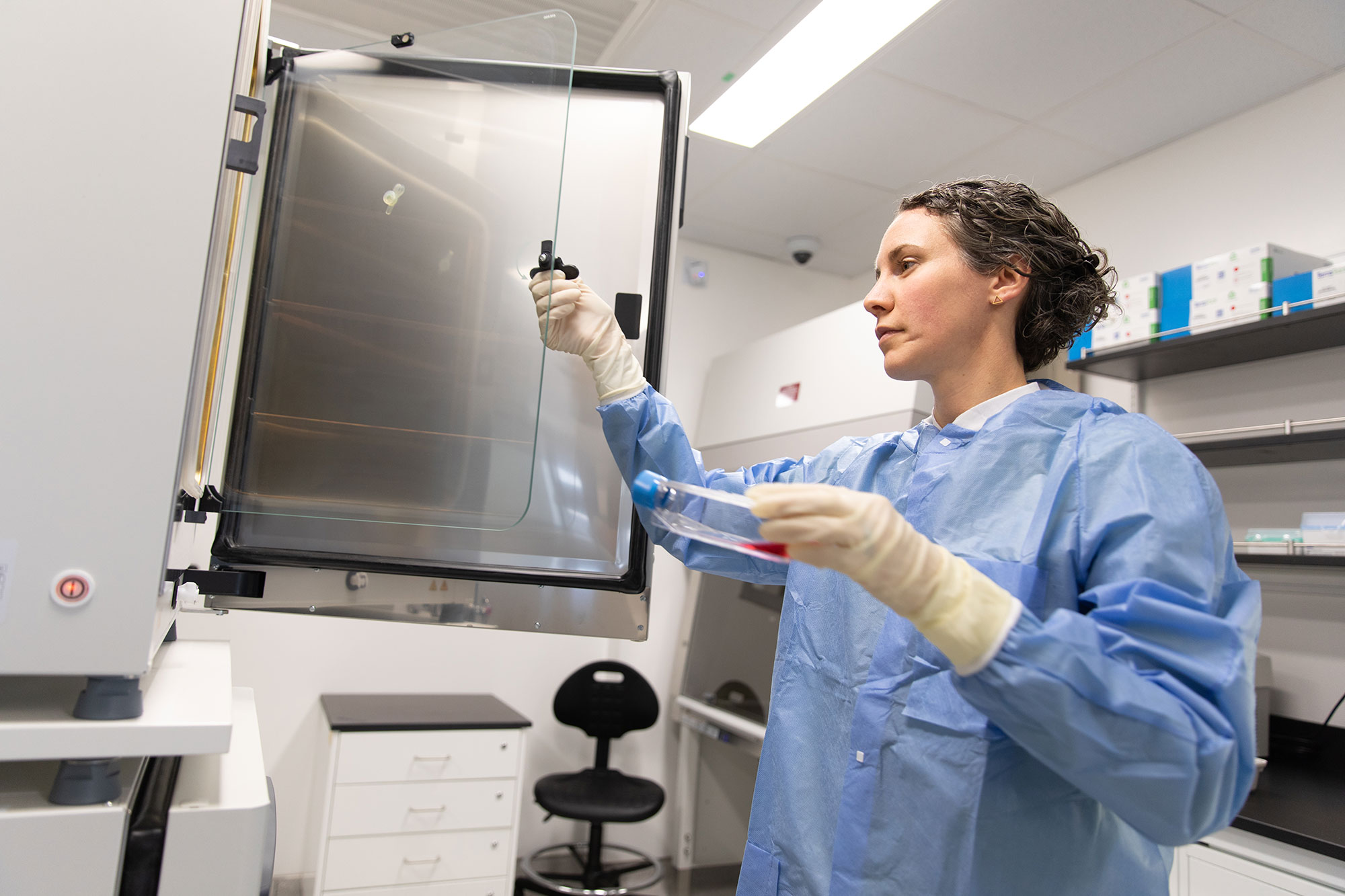

Her lab is conducting two unique experiments in the ImPaKT Facility to test this theory.

First, her team is getting foreskin tissues from Ugandan men who have been identified to have a high or low burden of anaerobes through Prodger’s collaboration with the Rakai Health Sciences Program in Uganda. The tissues will then be exposed to relevant strains of HIV to see if the men with anaerobes are more susceptible to infection.

“That’s a big way that the ImPaKT Facility comes in, because we need a containment facility to do these infection experiments,” she said.

For the second test, her lab is creating what Prodger calls the ‘3D in vitro foreskin model.’ They’re using tissue engineering to reconstruct an artificial foreskin and then culturing whole polymicrobial communities on top of the tissue to better recreate real-life interactions.

“It’s going to allow us to develop a paradigm-shifting 3D culture model where we can study this bacterial-human interaction, where both the bacteria and the human cells are alive and able to respond to one another,” Prodger explained. “It’s very novel because we’re going to inoculate with the whole polymicrobial communities as opposed to just bacterial products or individual bacteria of interest.”

Her team can then test which anaerobes or combinations of anaerobes might be leading to the inflammatory immune responses that contribute to HIV susceptibility.

Additionally, Prodger can use the model to screen potential antimicrobials for their ability to selectively remove pathogenic anaerobes and even add immune cells to the co-culture and examine their response. The model will also let the team observe the barrier function of the skin.

"I saw the devastation that this virus had on sub-Saharan Africa, and I felt like that was what I wanted to work on for the rest of my life."

– Jessica Prodger, PhD

Prodger was initially drawn to HIV research in the early 2000s in an effort to address the then 10/90 gap, where only 10 per cent of the world’s research dollars were being spent on issues affecting individuals in developing countries, where 90 per cent of deaths due to preventable diseases occurred.

The desire to fight this discrepancy led her to Uganda in the mid-2000s during her graduate studies. She saw first-hand the devastation HIV had on a country where antiretroviral medication had yet to become widely available.

“I saw the devastation that this virus had on sub-Saharan Africa, and I felt like that was what I wanted to work on for the rest of my life,” Prodger said. “Finding ways to prevent that from ever happening in the first place, and then finding a cure for all those people so they don’t need lifelong treatment.”

It’s this experience that continues to inspire Prodger today, with ImPaKT Facility opening up new possibilities for her research.

“The ImPaKT Facility will have dedicated facilities for my bacterial-human cell co-culture, which is a really big deal to me,” she said. “The Facility also gives me access to state-of-the-art imaging equipment that a relatively junior investigator such as myself simply would not have access to otherwise.”

Another benefit to Prodger is the collaborative aspect of the new facility.

“The shared research space is so important for bringing new ideas and new life to existing research programs,” she said. “The ImPaKt Facility is going to attract researchers from incredibly diverse backgrounds, investigating a huge range of pathogens, using quite a number of rare, cutting-edge pieces of equipment.”

The tools and environment in the ImPaKT Facility will help Prodger as she continues her mission of developing ways to prevent HIV transmission. Still, the impact of her microbiome work expands to other infections as well and has direct implications for treating bacterial vaginosis in women.

“These microbes are so essential to our health and interact with all of our cells in so many ways,” Prodger said. “But they’ve been previously overlooked in a lot of our research, and they may be the missing key to so many different health conditions.”